The purpose of this blog is to bring the heavens down to the Shabbat table....please share....

Imagine a project at Harvard to convene the greatest scholars in every field over a period of 100 years in order to create an encyclopedia of their collective knowledge. Who wouldn't want to see the final product?

Imagine a project at Harvard to convene the greatest scholars in every field over a period of 100 years in order to create an encyclopedia of their collective knowledge. Who wouldn't want to see the final product?

This is the Talmud: a collection of wisdom that would surprise experts in any discipline, including law, ethics, psychology and economics. In the realm of cosmology, too, the Talmud makes assertions — sometimes literal, sometimes metaphorical, and sometimes both.

To give one example, consider the Talmudic estimate of the number and distribution of stars in the universe.

In order to appreciate this passage, bear in mind two things.

First, the bulk of Talmudic wisdom is claimed to be a transmitted tradition, from Moses to Joshua, to the prophets, to the Elders, to the Great Assembly, and then to a chain of scholars until the completion of the Talmud 1,500 years ago. Hence it is called the "Oral Torah."

Second, consider the limitations of science 1,500 years ago: the telescope was invented in the 16th century, and the number of stars visible to the naked eye is approximately 9,000.

So what did the ancient rabbis say about the number of stars?

In Tractate Brachot, page 32b, the Talmud records a tradition, in the name of Rabbi Shimon ben Lakish, that there are roughly 10^18 stars in the universe. This number is remarkably big and much closer to the current scientific estimate of 10^22 than common sense would allow.

Now, although it is interesting for an ancient people to have such a large estimate, this single coincidence could perhaps be explained as an extremely lucky guess. Never mind that no other ancient people had an estimate anywhere near this order of magnitude, nor did they have a conventional way to write such a number.

(I posted this passage on a discussion board of professional astronomers and no one could identify a single other ancient culture with remotely similar numbers.)

However, the Talmud doesn't merely give a raw number. The passage explains that the distribution of stars throughout the cosmos is neither even nor random. Rather, it states that they are clustered in groups of billions of stars (what we call galaxies?), which themselves are clustered into groups (what astronomers call galactic clusters?), which in turn are in mega-groups (what we call superclusters?).

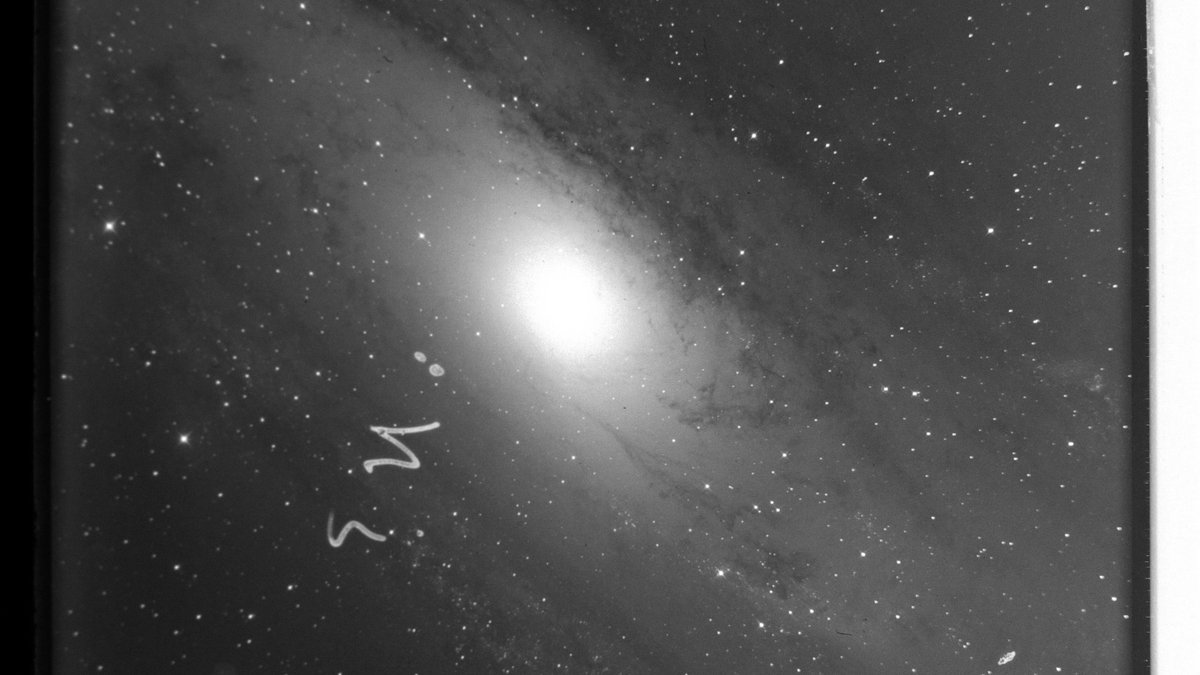

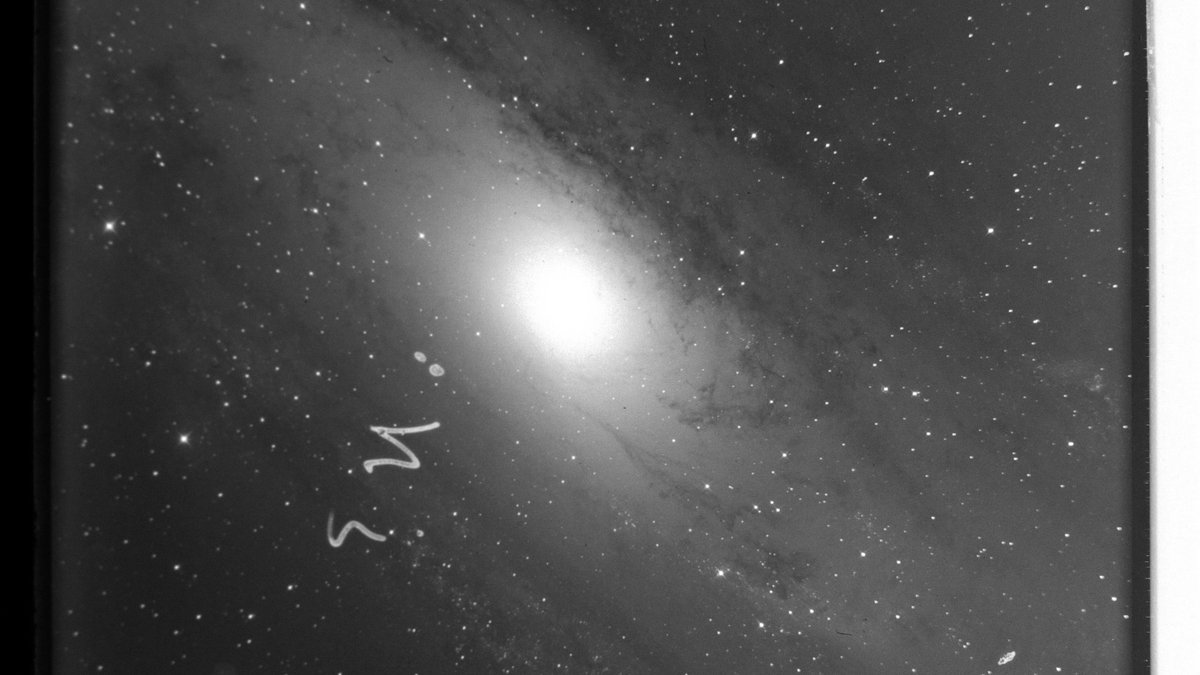

To describe the stars as clustered together, both locally and in clusters of clusters, was far beyond the imaginations and the telescopes of scientists until Edwin Hubble's famous photographs of Andromeda (pictured above) in 1923. Galactic clusters and superclusters have been described only in the past couple decades.

Now, the Talmud puts the number of galaxies in a cluster at 30, the number of clusters in a supercluster at about 30, and that superclusters are themselves grouped into a bigger pattern of about 30 (megasuperclusters?) of which the universe has a total of about 360. Thus, the Talmud appears somewhat consistent with one major theory that the overall structure of the universe is shaped by the rules of fractal mathematics. I showed this data to numerous astronomers around the world and the consensus is pure astonishment.

Could it be that Rabbi Shimon ben Lakish made an extremely lucky guess? It's hard to understand how. Perhaps had he had used a number that had symbolic significance in Judaism, such as seven, 10, 18 or 40. What is the significance of the number 30? To my knowledge, there is no symbolic or religious reason for choosing that number. It therefore seems to me to be exactly what it claims to be: a conscientious oral transmission of a received tradition, rather than simply one person's guesstimate.

Moreover, Rabbi Shimon had a reputation for impeccable honesty; it is unthinkable that he would have invented these numbers or guessed without telling us so. In my opinion, the intent of the passage is to convey an oral tradition.

Question for your table: Does Rabbi Shimon want us to take him literally, or is his teaching an allegory that we should interpret? If it's an allegory, what's the meaning?

It seems to me that both could be true. He may indeed be transmitting an oral statement of scientific fact while at the same time intending to to teach a moral lesson — namely, that the vastness of the Cosmos stands in contrast to the uniqueness of Earth, of human life, of the Jewish People, and of the Torah.

Therein lies the secret of tomorrow night's festival of Shavuot: There is something special about the Torah (and rumors of its demise have been greatly exaggerated!). The Torah is much, much more than a mere "cultural expression" of one tiny group of ancient people, so numerically small that we reminded Mark Twain of a "nebulous dim puff of star dust lost in the blaze of the Milky Way."

This passage about the stars is a mere five Talmudic lines, itself about as significant as a puff of star dust. But it also hints to the treasures available to those who seek them. Shavuot is a great time to begin.

Shabbat Shalom and

Chag Sameach

Appreciated this Table Talk? Like it, tweet it, forward it....